Key takeaways

- We all know what is driving the market selloff, COVID-19, but who is doing the selling?

-

Surprising many, passive ETFs have seen net inflows during March, suggesting individual investors are acting as a market stabilizing force.

-

The current bear market seems to be propelled by short-term traders and institutions, combined with a likely pullback of share buybacks by corporations.

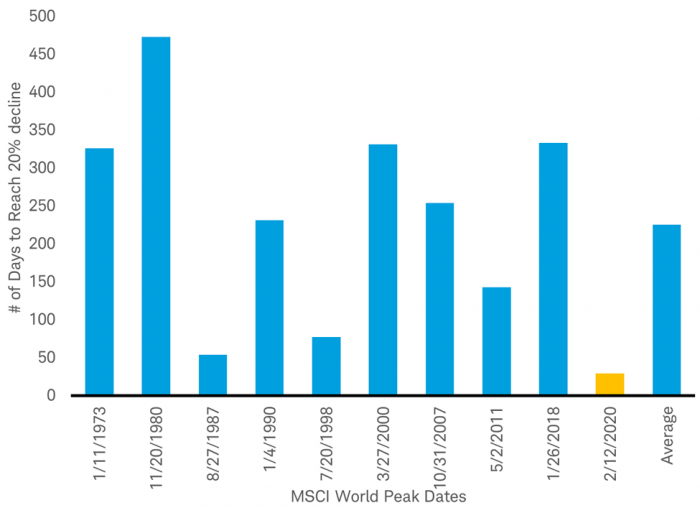

Since U.S. and developed international stock markets peaked this year in February, they fell 27% through the closing low this past Thursday. A bear market is declared once they reach the 20% threshold. Historically, it takes an average of eight months to enter a bear market. This time it took less than one month—the fastest ever.

Fastest bear market ever

Source: Charles Schwab, Factset data as of 3/13/2020. MSCI World Index data since 1/1/1970.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

We all know what is driving the market selloff: the efforts to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 pulling the global economy into a recession, the depth of which is hard to gauge at the present time. But are all market participants selling on the grim news? Surprisingly, that doesn’t appear to be the case. Examining which market participants propelled the fastest bear market over the past month may give us some insight to the current situation and may tell us what to expect in the difficult months ahead.

Was it passive (individual) investors?

In recent years, the rising popularity of passive investing (a strategy that tracks a market index) brought criticism that the strategy could amplify market momentum during the next downturn. In part, the concerns were motivated by a perception that individuals are quick to sell when returns suffer, and passive equity funds (like ETFs, exchange traded funds) may be forced to sell in periods of stress, when liquidity is poor, worsening a market downturn. Passive investing was relatively small (compared to active investing) when the financial crisis began 2008, and simply tiny when the dotcom bubble burst in 2000. But over the past 10 years, it has become a major trend among investors.

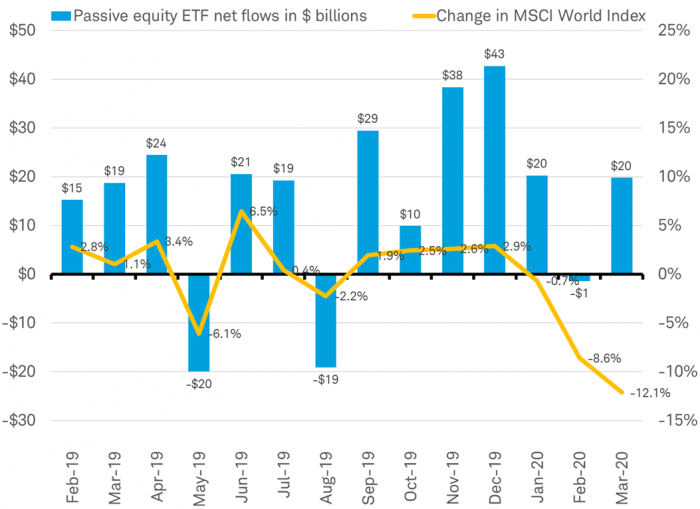

The criticism may not be founded, as market performance and ETF flows recently seem to be practicing some social distancing, as you can see in the chart below. Surprising many, passive ETFs have seen solid net inflows during March as the bear market took hold, according to daily ETF data tracked by Bloomberg. As the global stock market plunge accelerated last week, equity ETFs took in $9 billion. Predominantly, these flows have been into the broad, unlevered ETFs, which tend to be favored by long-term individual investors. So the rise of passive investing does not appear to be fueling the downturn—in fact, the opposite appears to be the case as they act as a stabilizing force.

Monthly net cash flows to passive equity ETFs and stock market performance

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 3/14/2020.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Of course, passive investors aren’t just buying equities. So far in March, some of the total net flows to passive ETFs went to perceived safe havens like bonds and precious metals, although the vast majority (nearly 80%) went to equity ETFs. While March data is not yet available for mutual funds, passive mutual funds saw strong net inflows in February (more than offsetting the modest outflows from active equity mutual funds). Whether investors are choosing the more liquid ETFs over mutual funds, the trend seems to be a net positive inflow for passive equity investments.

Was it institutions?

In contrast to the inflows to the ETFs that tend to be favored by long-term individual investors during the selloff, the leveraged and sector-specific ETFs preferred by traders have generally seen outflows and inverse ETFs that short the stock market have seen inflows.

Congressional testimony from market structure research firm Tabb Group in 2012, estimates that computer-driven, high-frequency trading accounted for more than half of all U.S. equity trading volumes annually from 2008-12, noticeably rising when markets fell. Both the high volumes and outflows from specific vehicles could mean that much of the recent sell-off and volatility may be short-term institutional trading activity.

Was it corporations?

Another driver of the market weakness may be that the biggest buyers of stocks in recent years—the companies themselves—may now be holding back from the market. There may be fewer buybacks by corporations concerned about keeping cash on hand.

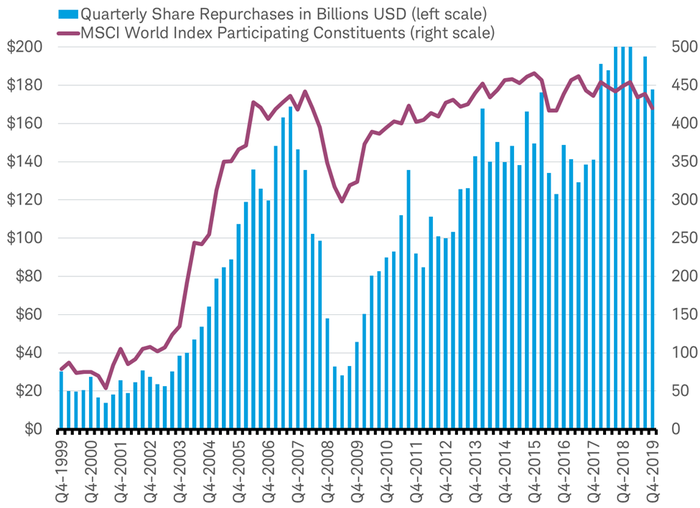

Because it is reported in quarterly earnings announcements, buyback data has a lag, making it difficult to track them across the entire market in real time. History shows that corporations tend to trim buybacks during bear markets, as you can see in the chart below. The tendency for companies to buy their shares as the market is rising—and then back off as the market falls—may be adding to the market volatility.

Company Buybacks historically held back in bear markets

Who is driving and what’s ahead?

The fastest bear market ever seems to have been driven by short-term traders, rather than long-term individual investors. Are individual investors just slower to react and will now begin to sell and send the stock market down further? Recent history suggests this may not be the case. The rapid rebound after 2018’s fourth quarter drop of almost 15% (as well as other similar sharp declines) have shown investors have been rewarded for sticking to their long-term plans. Individual investors, and their advisors, seem more resilient than in the past.

Longer-term investors may be focused on the duration of the current decline rather than its depth. Markets may have further to fall, but they may not stay down for the rest of the year barring a severe and prolonged global recession. The last major bear market began in October 2007 and didn’t bottom for one and a half years, as major imbalances had to be corrected. Today, the global economy faces fewer such imbalances. A short duration drop by nearly any amount is easier on long-term investors than one that lasts for years. Although another sharp decline could change the behavior of some individual investors, many will likely continue to make regular retirement contributions.

Fund flows reveal that passive investing has not contributed to the fastest bear market ever and that most individual investors have not been panicked into selling by the downturn and alarming headlines surrounding COVID-19. It also shows us that those individual investors that are hanging in there are not alone.